Online Privacy Through OPSEC and Compartmentalization: Part 1

Advanced

mirimir (gpg key 0x17C2E43E)

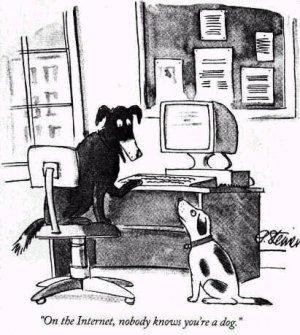

Privacy and anonymity on the Internet are perennial clickbait topics. At least, that’s been the case since some of the Eternal September crowd figured out that ‘On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.’ might be an unrealistic expectation. We’ve seen the warnings: ‘You have zero privacy.’ [1999]; Google’s ‘Broken Privacy Promise’ [2016]; ‘confronting the end of privacy’ [2017]; ‘privacy is dead’ [2017]; and ’technology can’t fix it’ [2017]; ‘Privacy as We Know It Is Dead’ [2017]. There was Eric Schmidt’s classic rationalization, ‘If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.’ [2009]. And recently, there’s been hand wringing about ‘anonymous harassment’ [2015] and how ‘anonymity makes people mean’ [2015]. For a more nuanced discussion of online ethics, see ‘Social Networking and Ethics’ [2012/2015]. In any case, leaving aside argument about whether online anonymity is “good” or “bad”, there’s no doubt that it can be a prudent and effective strategy [2017]. And in any case, there’s nothing new here. These were contentious issues in the 1780s, during public debate on ratification of the US Constitution. But hey, articles in The Economist are still published anonymously:

The main reason for anonymity, however, is a belief that what is written is more important than who writes it.

Why Mass De-anonymization Is Far Likelier Than You Might Expect

I’ve written a lot about online privacy and anonymity. Lately, however, I’ve focused primarily on matters of technical implementation. But a recent article about mass de-anonymization has moved me to write more about strategy and tactics. The article is based on a paper by Jessica Su and coworkers about de-anonymizing users by correlating their social media participation and browsing history. That’s too perfect a teaching opportunity to pass up. Anyway, the abstract begins:

Can online trackers and network adversaries de-anonymize web browsing data readily available to them? We show—theoretically, via simulation, and through experiments on real user data—that de-identified web browsing histories can be linked to social media profiles using only publicly available data.

Web browsing histories are collected by ISPs, the online advertising industry, at least some anti-malware firms, and various TLAs. So everyone online is vulnerable to multiple adversaries, who may collude, and leverage complementary data.

Our approach is based on a simple observation: each person has a distinctive social network, and thus the set of links appearing in one’s feed is unique. Assuming users visit links in their feed with higher probability than a random user, browsing histories contain tell-tale marks of identity. We formalize this intuition by specifying a model of web browsing behavior and then deriving the maximum likelihood estimate of a user’s social profile.

OK, but this assumes that people are naive. Using one’s real name online, with just one social network, is an obvious vulnerability. And it’s one that’s easily fixable, as I explain below. Basically, you just replace user/person with persona, use as many of them as you like, and make sure that they’re not associated with each other.

We evaluate this strategy on simulated browsing histories, and show that given a history with 30 links originating from Twitter, we can deduce the corresponding Twitter profile more than 50% of the time.

Impressive. So much for the dismissal that browsing history isn’t `sensitive information’ [2017]. But even so, each user could have several online identities aka personas. Each persona would have its own Twitter account, its own social network, its own set of interests, and so on. And each persona would access the Internet in a different way, using various VPN services, Tor, and combinations thereof. So each persona would have its own browsing history, potentially unrelated to the others.

To gauge the real-world effectiveness of this approach, we recruited nearly 400 people to donate their web browsing histories, and we were able to correctly identify more than 70% of them.

Impressive, indeed. But again, these were naive subjects. I can’t imagine that they were warned, and given the opportunity to be deceptive.

We further show that several online trackers are embedded on sufficiently many websites to carry out this attack with high accuracy. Our theoretical contribution applies to any type of transactional data and is robust to noisy observations, generalizing a wide range of previous de-anonymization attacks.

That is problematic, for sure. ISPs also collect and sell browsing history. Some anti-malware firms may do so, as well. And then we have various TLAs, which likely collect whatever they can, however they can, and from wherever they can.

In the paper’s introduction, Su and coworkers note:

In this paper we show that browsing histories can be linked to social media profiles such as Twitter, Facebook, or Reddit accounts. We begin by observing that most users subscribe to a distinctive set of other users on a service. Since users are more likely to click on links posted by accounts that they follow, these distinctive patterns persist in their browsing history. An adversary can thus de-anonymize a given browsing history by finding the social media profile whose

feedshares the history’s idiosyncratic characteristics.

That’s arguably not very surprising. It’s just what people do. Or at least, that’s what naive people do. And then they point out:

Of course, not revealing one’s real-world identity on social media profiles also makes it harder for the adversary to identify the user, even if the linking is successful. Nascent projects such as Contextual Identity containers for Firefox help users more easily manage their identity online 5. None of these solutions is perfect; ultimately, protecting anonymity online requires vigilance and awareness of potential attacks.

That’s excellent advice, for sure. But pseudonymity alone is a fragile defense. Once one has been de-anonymized in any context, everything is de-anonymized, because it’s all tied together. There is no forward security. Far more robust is to fragment and compartmentalize one’s online activity across multiple unlinked personas. With effective compartmentalization, damage is isolated and limited. And overall, it’s essential to implement and practice strong Operations Security (OPSEC). But first, before getting into specifics, it’s instructive to consider some examples, showing how easily and spectacularly online anonymity can fail.

Next Articles

- Online Privacy Through OPSEC and Compartmentalization: Part 2

- Online Privacy Through OPSEC and Compartmentalization: Part 3

- Online Privacy Through OPSEC and Compartmentalization: Part 4

Here to learn?

Consult our guides for increasing your privacy and anonymity.

IVPN Privacy GuidesSuggest an edit on GitHub.