Online Privacy Through OPSEC and Compartmentalization: Part 2

Advanced

mirimir (gpg key 0x17C2E43E)

Examples: How Easily and Spectacularly Online Anonymity Can Fail

To illustrate how online anonymity can fail, I have researched several examples. The mistakes made provide useful context for the discussion and recommendations that follow. The examples all involve criminal prosecutions, because that’s what generally gets reported. Proceedings in many jurisdictions are largely public, and crime reporting is always popular. Anonymity failure per se isn’t newsworthy, and information may be suppressed. Even so, public data about criminal prosecutions may be misleading. Some evidence is typically under protective order. Also, investigators may have employed parallel construction to protect sources and methods that are sensitive or illegal. Such evidence is not even presented to courts, but merely exploited to obtain usable evidence. But what we have is what we have. Finally, hindsight is of course 20/20, and I intend no disrespect to anyone involved in these examples.

Example #1: Silk Road

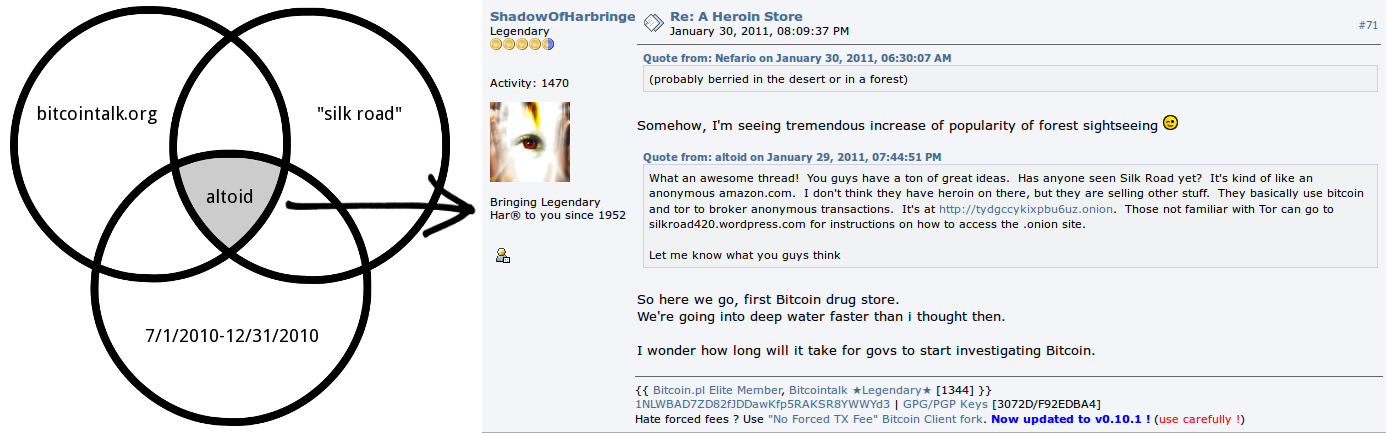

Consider how FBI investigators identified Ross Ulbricht as Silk Road’s founder, later known as Dread Pirate Roberts. As explained in the FBI complaint, he had promoted Silk Road on the Shroomery Message Board and Bitcoin Forum in January 2011, using the handle altoid. Silk Road had never before been mentioned on either site. The posts are still there, so you can follow the path yourself. In Google Advanced Search, specify the exact phrase silk road and the site bitcointalk.org. Execute the search. Then click Tools, and look at custom date ranges around 2011, when Silk Road opened for business. For the range 7/1/2010-12/31/2010, the first result is A Heroin Store - Bitcointalk.org. Search the page for silk road, and you see this post from ShadowOfHarbringer, quoting altoid:

Has anyone seen Silk Road yet? It’s kind of like an anonymous amazon.com. I don’t think they have heroin on there, but they are selling other stuff. They basically use bitcoin and tor to broker anonymous transactions. It’s at http://tydgccykixpbu6uz.onion. Those not familiar with Tor can go to silkroad420.wordpress.com for instructions on how to access the .onion site.

Someone (presumably altoid) has deleted the actual post. Just quotes by ShadowOfHarbringer, sirius and FatherMcGruder remain. I’ll say more about that, later. Here’s a diagrammatic representation of the search process:

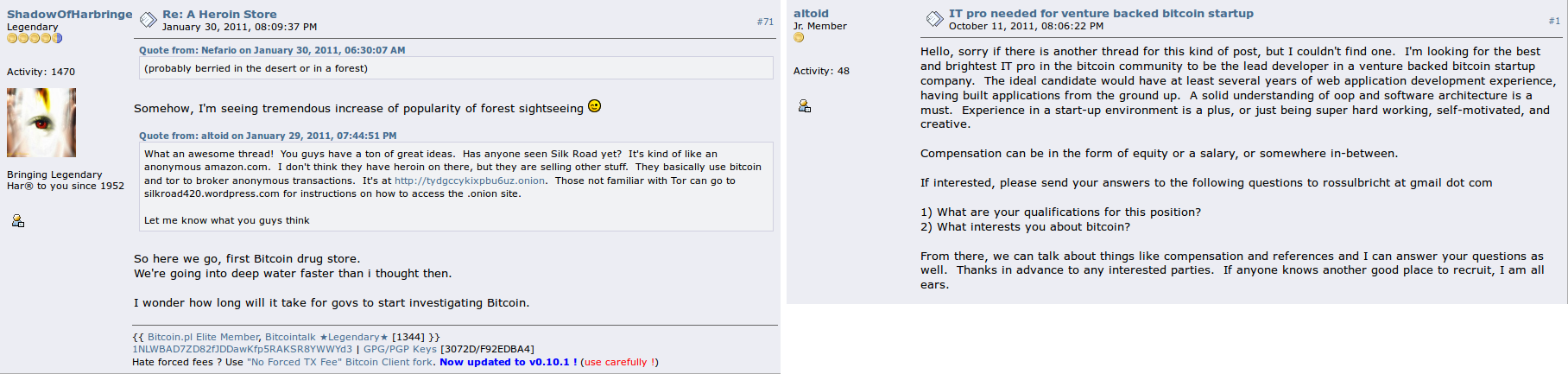

That alone wasn’t a fatal error. I mean, who is altoid? But now look at what else altoid posted on Bitcoin Forum. In particular, look at his last post, dated 11 October 2011: “I’m looking for the best and brightest IT pro in the bitcoin community to be the lead developer in a venture backed bitcoin startup company. … If interested, please send your answers to the following questions to rossulbricht at gmail dot com”. Whoops. Now the FBI had a link from Silk Road to Ross Ulbricht.

So how does someone accidentally link their meatspace email address to the development of Silk Road, a Heroin Store? I have no clue. Perhaps relevant is the fact that he registered the new account silkroad on 28 February 2011. He subsequently used the silkroad account for Silk Road matters, and the altoid account for general Bitcoin ones. I’m guessing that it was sometime in Spring 2011 that he deleted his post about Silk Road in the altoid account. But somehow, he didn’t notice that others had quoted it. The silkroad account was last active on 25 August 2011, about six weeks before the fateful IT pro post by the altoid account. Maybe he just forgot which account had posted what.

The timeline of the FBI investigation isn’t clear from the complaint, but another key win was finding the server. That was far too easy. Agents testified that the server leaked it’s actual IP address, bypassing Tor. It seems that they read about the leak on reddit. They don’t say exactly how they forced the leak, but I suspect that it involved a web server misconfiguration like this. At the FBI’s request, Reykjavik police provided access to the server. And the FBI imaged the disk.

That was a seriously boneheaded mistake. I mean, it was clear by 2012 that Tor onion servers should not have public IP addresses. I recall seeing a guide about that in 2010-2011, either on The Hidden Wiki or Freedom Hosting. But anyway, bad as it was for the FBI to have that data, how did they figure out that Dread Pirate Roberts was Ross Ulbricht? Other than the altoid screwup, I mean. Well, the complaint alleges that the server’s ~/.ssh/authorized_keys file contained a public SSH key with user frosty@frosty. So apparently, the FBI googled for stuff like frosty tor. And bam, they found this 2013-03-16 post by frosty on Stack Overflow. That’s still on the first results page. Also, the PHP code in that question is reportedly similar to what FBI investigators found on the server. And being the FBI, it wasn’t hard for them to learn that Ross Ulbricht owned the account (with email frosty@frosty.com). Now they had two independent links from Silk Road to Ross Ulbricht.

And there was a third link. Ross had apparently ordered fake IDs from Silk Road. But DHS opened the package, and dropped by to question him. He denied responsibility, and noted that anyone could have bought the fake IDs on Silk Road, and had them sent to him. That seems reasonable, no? I mean, a Ukrainian hacker did have heroin sent to Brian Krebs, and then had him swatted. But whatever. Silk Road went into the DHS agent’s report, and that eventually came back to bite Ross.

OK, so promoting your illegal darkweb site online is fine. And asking questions online about that site is also fine. But you want to be as anonymous as possible when you’re doing that stuff. And posting your meatspace Gmail address, or using a forum account registered with that address, is not anonymous. Ross was also careless in other ways about linking Silk Road to himself. If he had always worked through Tor (or better, hit Tor through a nested VPN chain) and had used pseudonyms to register with Stack Overflow and Bitcoin Forum, he might be a free man today. If you want to read more about Ross Ulbricht, the grugq has published a comprehensive (albeit dated) analysis. There are also decent articles in Wired and Motherboard, and Gwern’s analysis.

But wait. There’s another level of pwnage to explore. Maybe it’s simplistic to say that Ross Ulbricht is Dread Pirate Roberts (DPR). His attorneys argued that he was just a pawn, and that the real Dread Pirate Roberts was his mentor Variety Jones aka Cimon. For example, they presented evidence that someone was accessing the DPR account on the Silk Road forum for six weeks after Ross Ulbricht had been taken into custody. Plus voluminous chat logs between Ross Ulbricht, Variety Jones and others. It’s an interesting story, full of intrigue and drama, involving rogue FBI agents and so on. But here’s the relevant lesson: according to the complaint, Roger Thomas Clark was identified as Variety Jones “through an image of his passport stored on Ulbricht’s computer”. That is, “the Silk Road administrator insisted on his employees revealing their identities to him, though he promised to keep the copies of their identifying documents encrypted on his hard drive.” So maybe Variety Jones wasn’t a perfect mentor, notwithstanding his vision of a private digital economy. Still, he’s for sure no pushover.

If you’re interested in reading Variety Jones’ stuff from Silk Road Forums, the archives are here, and in more usable form, here. I gather that there’s also a lot in the chat logs that Ross Ulbricht retained. But I haven’t found a coherent standalone collection. For background, see Andrew Goldman’s The Common Economic Protocols and Toward A Private Digital Economy.

Example #2: KickassTorrents

Consider KickassTorrents. Artem Vaulin registered one of the associated domains (kickasstorrents.biz) using his real name. That’s basically the same error that Ross Ulbricht made with Stack Overflow, but it’s far more egregious here, because of the direct association. Also, logs from Apple and Facebook linked his personal Apple email address to the site’s Facebook page. That was another failure to compartmentalize his real identity from his illegal enterprise. But for those mistakes, KickassTorrents would likely be serving its users, and we would have likely never heard of Artem Vaulin.

Example #3: The Love Zone

Failure to compartmentalize also brought down The Love Zone and many of its users. Admin Shannon McCoole (skee) reportedly began his posts with the unusual greeting Hiyas (perhaps from Tagalog). That’s strange, but so what? Well, it seems that investigators unoriginally googled for skee hiyas, and found posts on various online forums by similarly named users, who used the same unusual greeting. On one of those forums, such a user had sought information about 4WD lift kits. So investigators then restricted their searches with suggested SKUs. And that led them to his Facebook page, where he had bragged about his vehicle. There, they also learned that he worked as a nanny. Busted.

OK, so it’s outstanding that they tracked him down. But even better, his mistakes are instructive. It’s much like the compartmentalization failure that pwned Ross Ulbricht. That is, Shannon McCoole linked his pedophile and meatspace personas through two factors: 1) similar usernames; and 2) unusual greeting. However, he apparently did successfully obscure his site’s IP address. So arguably, if he had used a distinct username and style (at least, a different greeting) on each online forum, he could have avoided arrest.

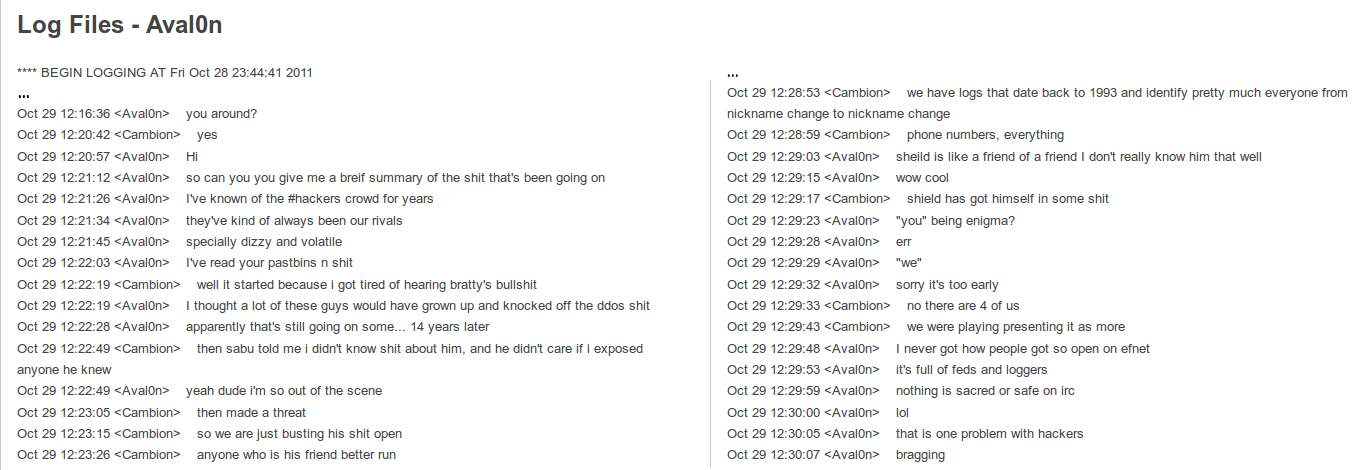

Example #4: Sabu de LulzSec

Sabu’s downfall clearly illustrates the roles of intentionality, trust and time. Sabu (Hector Xavier Monsegur) was born in 1983, and started hacking in his early teens. He reportedly hung out on EFnet IRC chat servers. Like most n00bs, was careless. At least once, he apparently made the mistake of logging in without obscuring his ISP-assigned IP address. And someone, perhaps the admin, was retaining chat logs. That’s to be expected. But based on those logs, they could link his various IRC nicknames, over time.

Years later, Sabu became famous through LulzSec. I gather that he was playing elite hacker to a crowd of script kiddies. That apparently offended some of his old EFnet associates. Plus the fact that LulzSec was causing trouble for them, professionally. And so they considered him a jerk, and eventually doxxed him.

Before researching this, based on casual reading, I had assumed that Hector had just been careless about OPSEC. But no, it’s not that Hector the LulzSec star was careless. It’s that Hector had been careless, many years before, when he was just a kid, playing at being a hacker. And that mattered, years later, because old associates could link his past personas back to the present. Still, he could have been more mindful of that risk, and so compartmentalized his personas more carefully across time. I mean, this guy had been hacking stuff for well over a decade!

Example #5: Sheep Marketplace

It’s arguable whether Tomáš Jiříkovský operated Sheep Marketplace, or merely provided hosting for the VPS that it ran on. But it’s pretty clear that he stole 96000 BTC from it, and then pwned himself when he cashed out. The story is instructive, and it illustrates how pride and greed can lead to stupidity and pwnage. Sheep Marketplace was created in March 2013. It grew modestly after Silk Road was pwned in October 2013. But before long, Tomáš had been doxxed as the alleged owner. Gwern Branwen bet that Sheep Marketplace would be dead within the year. In a later paste, Gwern alleged that someone had alerted the FBI that Tomáš had complained on sheepmarketplace.com in 2013 about the problems of running a Bitcoin-using hidden service. Also see this paste, perhaps from Gwern’s source. Anyway, Sheep Marketplace had started as a clearnet site, and then migrated quite obviously to Tor. And it was dead in far less than a year. Sheep Marketplace shut down less than two months later, on 03 December 2013, after claims of hacking and Bitcoin theft. But it’s more than a little suspicious that the Bitcoin price jumped from $200 to $1000 during November 2013. If one had been planning to take the money and run, that was arguably a good time.

In a vain attempt to recover lost Bitcoins, or at least to identify the thief, some redditors tracked suspicious Bitcoin through the blockchain. Although the thief apparently used Bitcoin Fog for obfuscation, 96000 Bitcoin predictably overwhelmed the mixer. So the stolen Bitcoin was traced to a wallet owned by BTC-e, a digital currency exchange. But there, the trail went dead. The BTC-e wallet identified by redditors was used generally in BTC-e operations. So it seemed likely that the thief had already cashed out. However, in contrast to the Bitcoin blockchain, BTC-e’s financial operations are anything but public. And now, the US has taken it down, and arrested one Alexander Vinnik. Allegations include money laundering and facilitation of criminal activity, such as ransomware and theft from Mt Gox. But maybe BTC-e isn’t yet entirely dead.

Anyway, in an 08 December interview in the Czech Republic’s major newspaper, Tomáš disavowed any role in Sheep Marketplace. However, by January 2014, Tomáš had been arrested:

Last year in January, a new bank account of 26-years old Eva Bartošová had a payment, that made Air Bank (Czech Bank) safety controls flash (an idiom). Almost 900 thousand Crowns from a foreign company that exchanges virtual bitcoins into real money.

The young woman could not credibly explain to the bank officers the source of the money. Only additional investigation revealed that millions already went using this road. And that behind it was a certain Tomáš Jiřikovský, that was connected by amateur internet investigators with stealing money from web marketplace Sheep Marketplace, where people traded in large numbers with the bitcoin currecy. The damage was described by the operators of the marketplace as more than 100 million.

…

The officers of Ministry of Finance’s Financial Analytical Office, that are detecting suspicious transactions, mapped how the Jiřikovský’s money travelled. They first left from the abroad company Bitstamp Limited, that is selling and buying bitcoins. The millions then arrived with several transactions either on the account of Jiřikovský and Bartošová, or on the account of the real estate company and the lawyer that worked on the house sale. Part of the money went to the original owner of the house, another part of the money went on her bank as one-time payment of a mortgage.

I’m guessing that Tomáš must have somehow transferred the money from BTC-e to Bitstamp. It didn’t help, however. Overall, this was a mind-boggling fail.

Example #6: Operation Onymous

In November 2014, hundreds of onion sites went down in Operation Onymous, an international effort involving the FBI and Europol. One of them was Silk Road 2.0 aka SR2. The scale of the operation was astounding. Nik Cubrilovic speculated that investigators had ‘simply vacuumed up a large number of onion websites by targeting specific hosting companies.’ But those who followed Tor carefully suspected a different sort of vacuuming. In July 2014, CMU researchers had canceled a Black Hat talk about ‘how hundreds of thousands of Tor clients, along with thousands of hidden services, could be de-anonymised within a couple of months.’. And a few days later, Roger Dingledine had posted about a ‘relay early’ traffic confirmation attack which had occurred in recent months: ‘So in summary, when Tor clients contacted an attacking relay in its role as a Hidden Service Directory to publish or retrieve a hidden service descriptor (steps 2 and 3 on the hidden service protocol diagrams), that relay would send the hidden service name (encoded as a pattern of relay and relay-early cells) back down the circuit. Other attacking relays, when they get chosen for the first hop of a circuit, would look for inbound relay-early cells (since nobody else sends them) and would thus learn which clients requested information about a hidden service.’ Yes, vacuuming.

Those suspicions were confirmed in January 2015, after SR2 admin Brian Farrell was arrested. The affidavit stated: ‘From January 2014 to July 2014, a FBI NY Source of Information (SOI) provided reliable IP addresses for TOR and hidden services such as SR2…’. And a year later, CMU’s role was confirmed: “The record demonstrates that the defendant’s IP address was identified by the Software Engineering Institute (‘SEI’) of Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) [sic] when SEI was conducting research on the Tor network which was funded by the Department of Defense (‘DOD’).” So how did the FBI know about results of DoD-funded research by CMU? The FBI says: “For that specific question, I would ask them [Carnegie Mellon University]. If that information will be released at all, it will probably be released from them.” Perhaps this was a failed attempt at parallel construction.

Example #7: AlphaBay

This is an especially sad example. AlphaBay became one of the largest third-generation dark markets after Silk Road got pwned. For about two years. Until the US took it down in July 2017, and arrested suspected co-founder Alexandre Cazes. As with my other examples, he had allegedly made a stupid mistake. He allegedly “included his personal email address in one of the site’s welcome messages”. I’m not sure which is more surprising, that he did that, or that it took investigators that long to find the clue. But the saddest part is that he reportedly killed himself after being arrested.

Example #8: Brian Krebs’ Blog

No, Brian Krebs has not been pwned for something delicious. But doxxing ‘cybercriminals’ is one of his perennially popular topics. And you will find many examples of compartmentalization failure. Such as these:

- Who Is the Antidetect Author?

- Who Hacked Ashley Madison?

- Who is Anna-Senpai, the Mirai Worm Author?

- Who Ran Leakedsource.com?

- Four Men Charged With Hacking 500M Yahoo Accounts

Next Articles

- Online Privacy Through OPSEC and Compartmentalization: Part 3

- Online Privacy Through OPSEC and Compartmentalization: Part 4

Here to learn?

Consult our guides for increasing your privacy and anonymity.

IVPN Privacy GuidesSuggest an edit on GitHub.